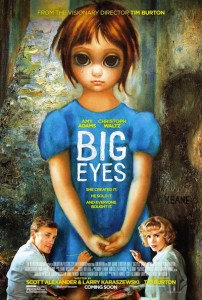

A Film Independent at LACMA World Premiere: Art and Dysfunction in Big Eyes

Last night, the Film Independent at LACMA screening series presented its very first world premiere with Tim Burton’s Big Eyes, which will open Christmas Day. Burton and stars Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz were in attendance. (Industry legend Harvey Weinstein was beaming in the audience.) And Film Independent curator Elvis Mitchell moderated a Q&A after the movie.

Adams stars as Margaret Keane, an artist whose paintings of waifs with big eyes gained massive popularity in the ’50s and ’60s. Waltz plays her husband, Walter—a failed painter but brilliant and charismatic businessman—who claimed credit for his wife’s work and found massive success in marketing her paintings and manufacturing cheap reproductions which, Burton said in the Q&A, could be found in “the dentist’s office, doctor’s office, grandmother’s house…”

“Keanes were everywhere,” Burton recalled. “It was kind of like Big Brother watching you; It was, like, very suburban art. It’s the only kind of art I would experience, sadly enough, growing up.” When screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who also penned the script for Burton’s Ed Wood 20 years ago, told him they were working on a screenplay about Margaret and Walter Keane, Burton says he was amazed. “With the art and the dysfunctional relationship, it seemed perfect. I understood it.”

Mitchell commented on the similarity between Ed Wood and Big Eyes—Burton’s only two films based on true stories—that both are about artists searching for art, whose ambition don’t quite match their limited talents. “Well, I understand that completely,” Burton joked. “That’s what I like about Ed Wood. He’s known to be a horrible director, but somehow, his work had an impact.” He pointed out that a lot of contemporary art is clearly influenced by Margaret Keane’s wide-eyed children, and added, “With Keane, even though I have major memories of [the artwork], I found it disturbing as well. So you get quite a response from people that love it or hate it… Those kinds of figures are quite interesting.”

Austrian-born Waltz was familiar with the big-eyed Keane paintings from his childhood, too: “We were taught to chuck it in the wastebasket—it’s kitsch. That’s American stuff,” he said to laughs from the audience. When Mitchell asked him how he was able to find the odious Walter within himself, Waltz said it was important that he didn’t judge the manipulative plagiarist—even after admitting that he could barely force himself through Keane’s autobiography, which he called “delusional rambling.” He never took that back, but did suggest that such an assessment is ultimately unproductive. “Having an opinion is fairly boring, you know,” he said. “I’m not called upon to have an opinion about a character I play. I actually want to understand, and I want to empathize—and that’s what we should all do with our fellow man anyway.” Ultimately, Waltz identified with Keane’s “despair to try to be an artist—and the understanding that you might not be one.”

Austrian-born Waltz was familiar with the big-eyed Keane paintings from his childhood, too: “We were taught to chuck it in the wastebasket—it’s kitsch. That’s American stuff,” he said to laughs from the audience. When Mitchell asked him how he was able to find the odious Walter within himself, Waltz said it was important that he didn’t judge the manipulative plagiarist—even after admitting that he could barely force himself through Keane’s autobiography, which he called “delusional rambling.” He never took that back, but did suggest that such an assessment is ultimately unproductive. “Having an opinion is fairly boring, you know,” he said. “I’m not called upon to have an opinion about a character I play. I actually want to understand, and I want to empathize—and that’s what we should all do with our fellow man anyway.” Ultimately, Waltz identified with Keane’s “despair to try to be an artist—and the understanding that you might not be one.”

Adams passed on the script when she first read it years ago; after playing a string of passive women, she was looking for stronger characters to take on. But when the script came to her a second time, she understood Margaret’s quietness to be strength. She also identified with Margaret as a fellow artist: “I’m an actress, so people never believe it, but I’m a very shy person,” Adams admitted, “and it’s something I really understand, about expressing yourself through your work and not necessarily wanting to be the figurehead of your work. So I understood that about Margaret.”

Margaret Keane is still alive and painting, and Adams met with her in preparation for the role. “She is so quiet, it takes about an hour to get eye contact,” Adams said. “She’s really quiet, and very generous, and she’s just not a large [personality]. She speaks through her art.”

The film culminates in an unbelievably wacky courtroom battle between the artist and her plagiarizing husband. Mitchell compared the sequence to the Three Stooges or the Marx Brothers, but Waltz insisted, “What we did was tame compared to what must have gone on in that courtroom back then.” Laughing, Adams said that the truth is stranger than fiction. “We toned down the courtroom scene,” Burton assured the audience. “I’ve always wanted to do a very serious courtroom drama.”

Mary Sollosi / Film Independent Blogger