From the Archives: Behind the Accent with Dialect Coach Jessica Drake

NOTE: The below piece originally ran in 2018. We’re re-posting it here with minor edits to the original text. Special thanks to author Su Fang Tham and subject Jessica Drake.

***

Dialect coach Jessica Drake has been working her magic behind the scenes for over 20 years. She’s done everything from helping craft Tom Hanks’ Alabaman drawl in 1994’s Forrest Gump to taming Andrew Lincoln’s Queen’s English into Rick Grimes’ American burr on the AMC mega-hit The Walking Dead. Her recent credits include work on TV’s Yellowstone and the features Honey Boy, Vice and Bohemian Rhapsody, among others.

Good accent work can certainly be key to selling an onscreen performance. But actors don’t always (or often) get the specifics right on their own—which is where experts like Drake come in. In today’s Detail Oriented, we’ll delve deep into the work that goes into getting the accents right, with a specific focus on how Drake helped Brit Tom Hiddleston successfully morph into country music legend Hank Williams for the 2015 biopic I Saw the Light.

JESSICA DRAKE

Dialect coaching is such a specific field within the film industry. How did you get started doing it?

Drake: I went to drama school for seven and a half years before graduating from Julliard. I mainly did regional theater in New York and then came out to LA. I suddenly found myself being an “LA actor” which is rough; there’s a lot of down time. So I started coaching. Actually, I started coaching when a friend from Carnegie Mellon, where I also trained, wanted me to help with her accent. I taught speech and dialect at UCLA, Cal Arts and started the Voice and Speech Department at the LA County High School for the Arts.

What sort of training did you have for this specific type of work?

Drake: Specifically, the speech training I had with Edith Skinner. The training with her is why I can do what I do today. I really learned phonetics, a lot of Shakespeare techniques like scansion and meter. Mastering all these requires tremendous specificity. Edith was dedicated to “the classic Skinner method for speech on the stage” which has often been misidentified as “Mid-Atlantic speech”—meaning, a mythical place between England and America. Edith focused on this sound specifically for what she calls “elevated texts” like Shakespeare and period plays, some that were not originally written in English but translated in a British style. For example: Chekov, Ibsen and Strindberg, where you can’t sound like you just left the mall yesterday. She did not like the idea of American actors feeling like they had to sound British. Well-known examples of actors who spoke in this style are Fred Astaire and William Powell. That’s what her style was similar to. I don’t get asked to teach this style very often now. It has to be a period piece. If you understand the basic sounds of an accent you can recreate it.

Do dialect coaches specialize in a family of languages and dialects—e.g. only the Latin-based romance languages and English? Or are you expected to handle everything from Haitian Creole to a Japanese dialect?

Drake: There are some who specialize in specific dialects, but I don’t. I can do any dialect as long as I have the core material: access to native speaker or audio samples. I need to be able to hear it. I’ve also had to make up accents and that’s really fun. For example, I’ve done it for sci-fi, and I did a Bible movie [The Nativity Story] and I completely invented an accent for it I called “Biblical Middle Eastern.”

Most of the films we see about Biblical times are done with British accents. How did this come about?

Drake: This goes back to a whole different time; studios in those days promoted the idea that movie stars were not like us. They were better than us. That was what the studios were all about. That had already existed on the stage for a long time, at least back to the 1860’s and probably way before that. I think actors were always doing something more elevated, probably. The American accent is a mishmash of all these different immigrant groups who have influenced how we speak today. We have enough trouble adhering to the idea of English as the official language of the U.S., let alone with the notion that it should be spoken a certain way. While in England, until the 1960s you couldn’t be on BBC if you couldn’t speak what was called “proper BBC English.”

How much of your acting background helps your coaching work?

Drake: If I’d never acted, I don’t know how I would do this job. You have to understand the actor’s process. So you have to tailor it to that individual and figure out what’s going to work for them. It’s important that I walk a mile in my client’s shoes. Actors are not impressionists—that’s a very different thing. You don’t want the actor to be confined. That’s partly where my acting background comes in.

How much does immersion and constantly listening to the accent you’re trying to mimic help with the end result?

Drake: It definitely helps, but it’s not always available. For example, we shot Forrest Gump in South Carolina and the movie takes place in Greenbow, Alabama. But sounding out the lines in a script phonetically is more helpful because ultimately, you have to be very specific to what you actually have to say [in the film]. Human beings are wildly inconsistent. If I show you six samples from the same town they would all sound a bit different. So the actor has to decide with the coach’s assistance. I let the actors lead me as to what works for them and what they feel is appropriate for their character.

Some people find accents more difficult to reproduce or mimic than others. What do you do in those situations?

Drake: You just try everything. You give them [the actor] audio samples, the transcripts, the visuals. You do drills and you try to find a way that works for the actor. In the end, the acting is more important than the accent. When an actor is thinking about their accent more than their acting, it results in what I call “dialect acting” and it’s usually pretty boring. Because they’re not living in the moment and being the actor they can be because they’re hung up on something technical.

When the accent isn’t quite there, does it take you out of the story?

Drake: I try not to pay too much attention to the accent when I’m watching a movie because I want to just be caught up in the story. I want to enjoy the performance. On films with enough of a budget, it can be fixed in ADR [automated dialogue replacement, where actors re-record their lines at a recording studio after the shoot -ed.]

On I Saw The Light, director/writer Marc Abraham has said that Tom Hiddleston really has a great ear, which made it easier for him to master the nuances of the Alabaman accent. What did it take to transform Tom Hiddleston’s crisp British English into Hank Williams’ Alabaman accent?

Drake: It was a low budget film and I only had six days to work with Tom before he had to record the first song for the film. When you’re working with a real-life character, you have to match a lot more than just the accent. You have to get all the nuances of their voice—pitch, rhythm, melody and phrasing. Every inconsistency of Hank Williams’ speech had to be mimicked in these songs. In a biopic, the hardest thing to get your hands on in terms of research is: What does this person sound like at the breakfast table when he or she isn’t in the public eye? If you try to match the public things people know as specifically as you can the audience will think, “Yeah, that sounds like him.” This will buy you some goodwill and they [the audience] will hopefully give you a little more slack in the scene when he’s having breakfast or fighting with his wife in their den.

Tom Hiddleston did all of his own singing—and yodeling!—in the film. What did it take to match Hank Williams’ speech patterns in song?

Drake: In real life, phonetic patterns in a dialect are not always being followed because human beings are inconsistent. That’s just as true in singing. Even within one sentence, a person can pronounce the same thing three different ways. So you have to look for all those inconsistencies when you play a real person, whereas when you’re just doing an accent, you have a lot more freedom. [In Forrest Gump] we just have to believe you’re from Greenbow, Alabama, which doesn’t even exist; we don’t have to believe you’re LBJ. So that’s the difference.

How does it work when you’re scouting for potential accents or dialects to use from real life people?

Drake: When you ask a regular person to read lines [from a script] they tend to sound wooden. Instead, I like to get them talking about anything that they’re enthusiastic about and can keep talking naturally, because I want to hear their genuine sound. I want them to forget they’re being recorded; otherwise, they may stiffen up.

I read that you broke down the script phonetically so that Williams’ speech patterns were literally spelled out on Hiddleston’s script pages.

Drake: We worked on what Hank Williams’ pronunciation and vocal patterns sounded like to Tom and then I worked on the entire script and wrote out all the lines phonetically for him. I have a [laptop] folder labeled “Hank sings” and another with “Hank speaks.” I would recognize the phonetic pattern to those sounds from Hank’s own words and we would replicate it to other words where it would fit phonetically. So Tom could apply those to whatever lines he may have needed to say in the film.

Lastly, how much ADR did you have to do on this film?

We didn’t do any ADR. He sounded great!

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. To support us with a donation, click here.

More Film Independent…

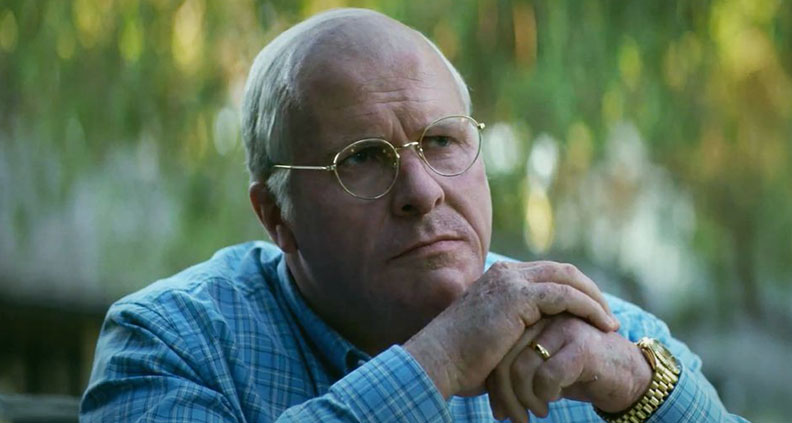

(Header: Tom Hiddleston and Elizabeth Olsen in I Saw The Light)