Hacking Film: A Brief History of Cheap and Free Editing Platforms, Part One

This is the first part of a two-part Hacking Film series about how—surprise!—its 2018 and you can have free and cheap editing and color-grading software from companies that used to charge a hundred thousand dollars for their products.

EDITING ON THE CHEAP?

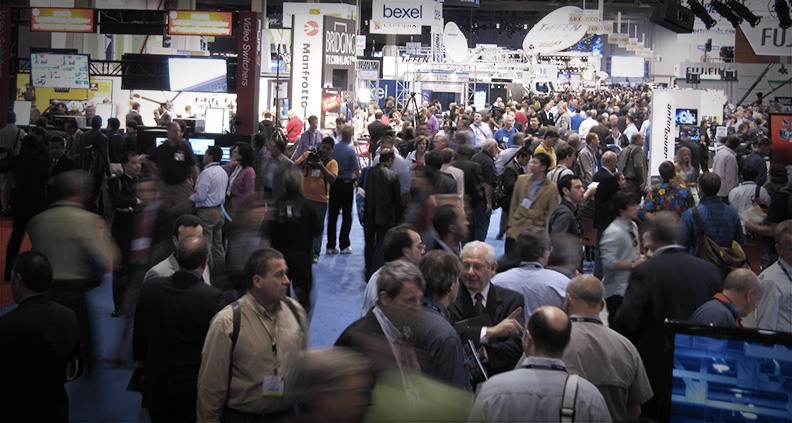

In 1989, Avid announced its Media Composer at the annual National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) convention in Las Vegas. There were other nonlinear editing systems at the time, but they were all incredibly expensive and didn’t offer much more than a few minutes of video storage.

At the time, Avid Media Composer offered up a collection of off-the-shelf and proprietary hardware and software, a Mac IIcx with two displays and 4GB of storage. You could digitize footage with a video deck plugged directly into the system. It was right at the threshold of acceptable visual quality to judge an offline edit, but it was good enough. And for the low, low price of $80,000, it was affordable enough to colonize commercial editing suites, TV stations, colleges and movie studios around the world.

But… it still took about five years for the video compressed of Avid’s AVR codec to be considered broadcast quality. In the interim producers had to do the online edit with analog video gear for their final master, and the millions of dollars in old film editing infrastructure still had a reason to exist—as did the high fees to get a project mastered.

For color grading, motion graphics and video effects, million dollar suites still reigned. The DaVinci Resolve system, for example, was a rarefied affair. With close to a quarter of a million dollars worth of gear and software to be installed in a dedicated color grading stage, these systems were found only in a handful of cities around the world—and available to only a handful of editors and producers.

In this world infrastructure was exclusivity, and there was a tight relationship between the engineers that built the machines and the facility personnel that worked them. It was a domain that was mostly male, affluent, white and urban. It was extremely technical and very expensive. It was exclusive by design, if not by intent. But those seats of Media Composer running on Macs and Window machines were the signal that this was all going to collapse—and that this collapse was going to happen faster than anyone could have guessed.

The causes are many, and I could write for days about all of them, but I want to focus on the fight between Avid and Apple. In part, because this is the part of the story I know best from experience…

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

There was a moment in the late ‘90s when you could lease an Avid system, stick it in a rented space in a three floor walk-up in lower Manhattan and hang a sign outside that said “Avid Off-Line Rental.” I know a number of editors who ran these Avid sublease situations who made enough money to pay for the rent, pocket some cash and have their own editing space to use for free whenever they needed it. They had to do some scheduling and management, but it was a tidy little ecosystem.

This was an explosive time in indie filmmaking, particularly for documentarians, but it also opened up opportunities for commercial editors, short filmmakers and feature directors. The days of VHS dubs and paper edits turned into time spent in cheap Avid suites actually cutting together your show. By the late ‘90s, Avid (and a few others) were claiming “broadcast quality” codecs. This meant either “uncompressed” video codecs, or variable 2:1 and 3:1 rates. This meant that you didn’t have to go back to the big, bad post house with millions of dollars with gear to do an “online” edit.

Avid was “online” now. The company gobbled up Digidesign and a bunch of other smaller software and hardware companies. They rounded out their suite of products as a single, turnkey post-production solution, and the comfy post houses with catered lunches were safe to continue charging expensive hourly rates

In 2001 I jumped shipped from running a post-house in SoHo to software development in Silicon Valley—I left behind a sinking ship of dedicated Avid hardware behind in New York City to join the Final Cut Pro development team at Apple.

BLUE AND SILVER BOXES

Final Cut Pro didn’t start life at Apple. In 1998, it was a product under development at Macromedia in San Francisco—a cross-platform product codenamed “KeyGrip.” The designer was Randy Ubillos, the same software developer who created the first three versions of Premiere. Apple acquired the product (and the team), and in 1999 the first version of Final Cut Pro, now Mac only, was released.

Here was a stable video editing product capable of capturing, storing, editing and outputting Firewire-based video with no need for additional hardware—all for $1,000. A year later Final Cut Pro 2.0 was released, designed to run inside of G3 and G4 PowerMacs—those plasticky blue and silver rounded towers.

Suddenly, the economics of the Avid infrastructure only made sense from the perspective of momentum and institutional bias, not from a price/performance standpoint. This is what I witnessed in the winter of 2001, when Digital Film Tree opened its doors in NYC—an entire facility built around Final Cut Pro 2, off-the-shelf Macs and cheaper prices for all things post. At first, the Avid houses ignored the problem, then cratered in the aftermath of the Web 1.0 bubble. The lean and cheap survived, and for the next seven years Final Cut Pro—the software solution made to sell G4’s—roared into post houses, TV studios and Hollywood.

While the big cities with their established brands and companies adjusted, something new happened. FCP running on a Mac meant that anyone, anywhere, could be a post house. Even as Avid held its position as the choice for serious professionals, millions of other people made movies that couldn’t ever make them before. The value of professional software was immediately pegged at a thousand dollars.

There was nowhere to go but down…

Stay tuned for Part Two of our two-part series, wherein we’ll explore where low-cost video editing went in the years in-between the start of the new millennium and now, including where the technology stands today—and how you can best use it.

Learn more about the evolution of filmmaking tech, including where we might be headed next, by checking out more of Eric Escobar’s Hacking Film series. To learn how to become a Member of Film Independent just click here.