Know the Score: Anatomy of a Great Film Score – ‘King Kong’

In our regular Know the Score series, composer and musician Aaron Gilmartin steps out of the scoring stage and explores, in detail, some important aspect of movie music. This month, a special monster-themed Halloween treat!

***

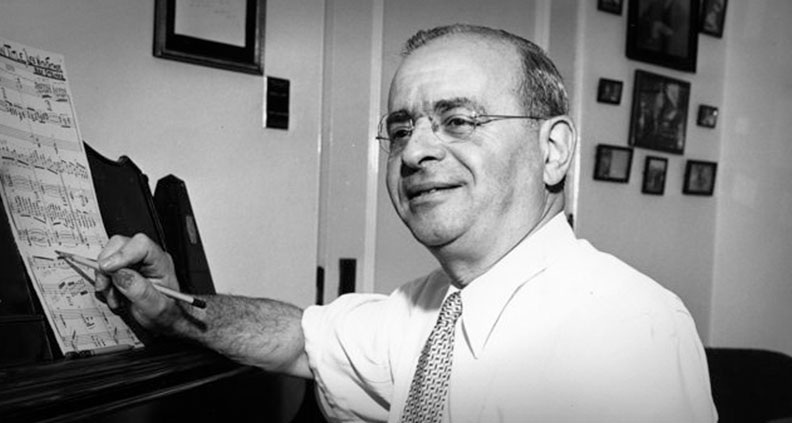

It’s easy to imagine that the importance of Max Steiner and his score for the 1933 giant ape classic King Kong is attributable to simple timing. The Austrian-born Steiner (1888-1971) arrived in Hollywood just as sound film was being born and coming into its own. And his music for Kong arrived just in time to accompany the emerging marvel of stop-motion animation and other special effects innovation in moving pictures.

But Steiner was a man of prodigious musical talent, work ethic and commitment to his craft. This sometimes caused him to neglect his home life but was perhaps something he felt necessary to do in order to take advantage of the opportunities he found during Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Steiner was born in Vienna, into a family of theater and entertainment movers-and-shakers. His grandfather (and namesake) Maximillian ran the Theatre an der Wien, where Johann Strauss composed operettas weekly for an adoring crowd. These included melodies we still hear today in pieces like “Die Fledermaus.” As a boy, Max knew Strauss and was deeply influenced by his music.

Grandfather Max also created a highbrow amusement park called “Venice in Vienna.” This is where our Max heard early music recordings from the a new Thomas Edison invention called the phonograph, as well as where he saw and heard African chants, dances and other musical traditions that would appear in his later compositions. Perhaps even more importantly for his future in Hollywood, he saw the new invention of Augusté and Louis Lumiére: their Cinématagraphe. Soon, Venice in Vienna was the site of Austria’s first moving picture theatre.

Max’s first published compositions came when he was nine-years-old. These were songs, and his imagination—fueled by the theme park exposure to other cultures—led him to write pieces that referred to the cultures of the world outside of Vienna. In time, he learned to write in the romantic style of the Viennese waltz and began to show a penchant for music with deep emotion.

After he left Vienna, Steiner worked in the theatre in London and later New York. In these relatively austere years, in comparison to his comfortable upbringing in Austria and later success in Hollywood, he honed many of the skills that would be so useful in dealing with the constraints of the film business.

Steiner would come to study all of Wagner’s operas assiduously and loved the impressionistic and avant-garde works of Debussy and Ravel. He learned early to imitate the sounds he loved and paid homage to many great composers in his scores, observing how their styles would support the story of a film and heighten the drama.

The first musical score in King Kong comes when the boat of the explorers arrives at the island where Kong lives. The name given the cue is “Boat In The Fog” and the orchestration here of sustained strings and harp arpeggios with ominous melody in winds and brass for me is reminiscent of Claude Debussy’s famous “La Mer (The Sea)”.

The head of RKO, David Cooper, was a fan of wall-to-wall music for his films, and for the most part so was Steiner. Yet in a display of restraint, Steiner showed his understanding of the power of silence; he proposed leaving the first 18 minutes of the film without music. He wanted the Depression-era metropolis of New York in the film’s first act to stand alone, bringing in the “dreamlike feeling” of his score when Kong’s action is finally en route to Skull Island.

As Stephen C. Smith puts it in his book Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywoods Most Influential Composer (2020), Steiner understood that Kong was both the antagonist of the film and, by its end, the tragic hero. The musical language would be both “impressionistic and terrifying,” using orchestration like Ravel and Debussy for the ocean scenes, then-modern dissonant music for the scenes of action, and a towerin Wagnerian leitmotif for Kong.

So—what, then, did Max Steiner bring to film composing that for some historians garnered him the moniker “The Father of Film Music”? It would be his application of leitmotifs, his novel and subtle use of orchestration and how he carefully synchronized his music with the action and emotion onscreen for a heightened psychological effect on his audience.

King Kong made Max Steiner’s name well known as one of the first great examples of the use of modern compositional techniques in cinema, even though the year before he inaugurated some of these techniques in his score for Symphony of Six Million. Steiner came along at a moment when a new art form—film with sound—needed a new synthesis of techniques that he was uniquely prepared to provide.

These skills required a sensitive and steady hand and only flourished because Steiner was such a prodigious and consistent productive force. Through his upbringing in Vienna and then career in the theatre in London and New York, Max learned the modern musical language including orchestration and the use of leitmotif to accentuate the emotion, psychology and arc of story in film. The score for King Kong is where all of these factors converged and his skills of composition came to fruition shaping the sound of Hollywood for decades to come.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. To support us with a donation, click here.

More Film Independent…

To learn more about Aaron Gilmartin, visit his website.