Notes on the Cinematographer: A Conversation With Nuri Bilge Ceylan

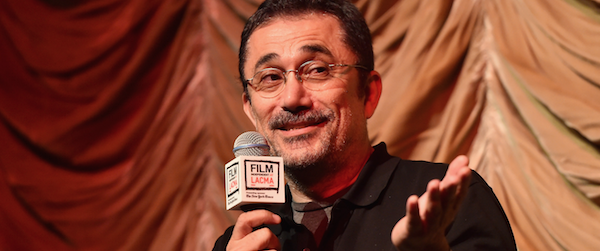

“I hope you are not sleepy,” said Turkish filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan as he took a seat on stage at the Bing Theater Tuesday night. He and Film Independent Curator Elvis Mitchell sat down for a discussion before the night’s screening—instead of after—because the film (Ceylan’s latest, Winter Sleep) “is a bit expansive,” as they both put it.

So before the audience settled in for the 192-minute opus and Palme D’Or winner, they listened as the two men discussed Ceylan’s camera movement, his background in photography, and his affection for the work of Yasujiro Ozu and Robert Bresson.

In the style of Bresson’s seminal Notes on the Cinematographer, here are several insights the Turkish director offered on the art and craft of filmmaking.

“The best thing about photography is that it is something you can do alone.”

Mitchell began the evening asking Ceylan about his beginnings as a photographer. Ceylan said he got into it because he wasn’t a social person and he liked the solitude the medium afforded him. He said snapping shots and developing the rolls was a kind of game to him at first, and it wasn’t until much later that he discovered it was also an art form.

“To move the camera smoothly is very expensive.”

When Mitchell asked if his photography background influenced his early features, Ceylan was hesitant to confirm the link. He agreed that because of their lack of camera movement, his early features do have a photographic quality, but insisted that this was less an artistic consideration than it was a matter of budget. “My mind was always thinking, even when I wrote the script, according to my budget. And according to my crew. My first feature film I shot with only two people. Myself and a focus puller. How can you move the camera?”

In his more recent features—Winter Sleep included—Ceylan’s camera has become much more fluid. When asked why he has gone the opposite direction from Ozu (who, by the end of his career, used only static frames), Ceylan again pointed to budget, saying that he places the camera on a pan-track in nearly every setup so that he’s ready to give the scene the emotional push it needs and doesn’t have to reset for the move.

“Literary dialogue is very difficult and generally doesn’t work in cinema.”

Ceylan said he first encountered Chekhov’s play, The Wife (on which Winter Sleep is based), 25 years ago, and had been thinking of making of film of it for much of that time. “Why I didn’t do it before? Because it’s a difficult story. It was difficult story and I didn’t trust myself before. And with time, when I felt more confident as a director, I thought, ‘I can try it now.’”

One of the major challenges of adapting the work was translating interior monologues to the screen. Ceylan said he put some of those passages into the dialogue, but much of it was cut. Even still, Winter Sleep contains several lengthy dialogue scenes, and those scenes were, for him, the reason for the film. “I wanted to express my love for literature and theatre in this film,” he said. “I tried to make these literary dialogues work in cinema. This was something I was very afraid of when I started this movie.”

“Seasons are one of the best creations of God for human psychology.”

And the seasons play a major part in Ceylan’s films. “I think the weather changes our psychology. So, just like in my life, I try to use this in my films, as an element of the psychologies of the characters.” In Winter Sleep, it’s a snowstorm that signals change between major characters. “You separate from your girlfriend or your lover and the next day you’ll see the world completely different, even if nothing changed. But in cinema, I want to emphasize this change, by changing the atmosphere also.”

“When I finish a film, I always think that it is terrible and unsuccessful.”

Mitchell asked Ceylan about his experiences at Cannes, where he has had no shortage of success. Winter Sleep was the big winner in 2014. His previous film, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, won the Grand Jury Prize (Cannes’ silver medal) in 2011. In 2009, Ceylan served on the festival’s jury. Asked which experience he most enjoyed, Ceylan said, without a doubt, being on the jury. “Because when you finish editing… you see mistakes all the time. So you think everyone will see only that. And in Cannes, you have to watch [the film] with the audience. And that’s something I hate… But se la vie. You have to do it. For the sake of the film.”

“I think everybody is quite lonely. It’s how I see life.”

As their conversation drew to a close, Mitchell took stock of Ceylan’s influences: Photography, Ozu, Bresson, Chekhov. He asked Ceylan if loneliness was something he is consciously trying to explore. “Yes,” said Ceylan solemnly, “that is something I have felt deeply since I was very young.”

Ceylan confessed that even in his happiest moments he feels deeply sad. “But I’m used to it,” he said with a shrug and a smile. “I’m peaceful with this feeling. And I think cinema, making films, helps me a lot to make peace with my melancholy. It’s like therapy.”

Tom Sveen / Film Independent Blogger