The Doc Life: The Legal Realities of True Crime Docs

Each month in The Doc Life, Film Independent blogger Anthony Ferranti dives deep into the how’s and why’s of nonfiction filmmaking, featuring advice and hard-won insight from top veteran and emerging documentarians. Enjoy!

***

As a kid lying on the living room floor in front of a behemoth TV, a root beer and bowl of sunflower seeds within easy reach, I’d regularly watch any one of the many popular crime dramas that were a staple of network TV in the ‘70s and ‘80s—shows like Columbo; The Rockford Files; Quincy, M.E. and Magnum, P.I. just to name a few.

In many significant ways, the true crime boom of our current age is far different from this bygone era of the TV procedural. But I do see a connection: both genres lay out compelling stories centered on transgressive criminal acts, slowly revealing the facts of each case and leading audiences to an often shocking final conclusion. But whereas TV writers craft fictional narratives that resolve within the hour, documentarians deal with real people—and can face real-life consequences for storytelling missteps.

Nonfiction filmmakers must always consider what potential pitfalls they may be facing in order to avoid legal jeopardy. So for this month’s Doc Life, I talked award-winning director and cinematographer Skye Borgman—whose Abducted in Plain Sight has captivated audiences since its Netflix premiere in January—and Lisa A. Callif, founding partner of Donaldson + Callif and go-to attorney for Hollywood’s most acclaimed independent producers.

We discussed what legal and creative considerations all would-be true crime documentarians should take into account before hitting “record.”

COLD CASES & RISKY BUSINESS

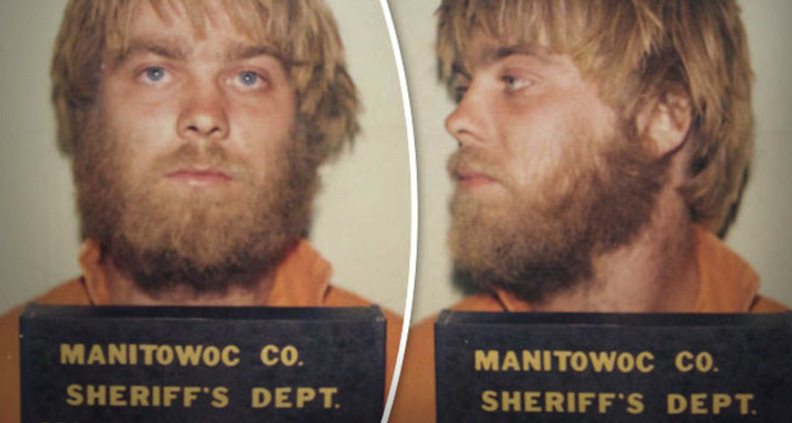

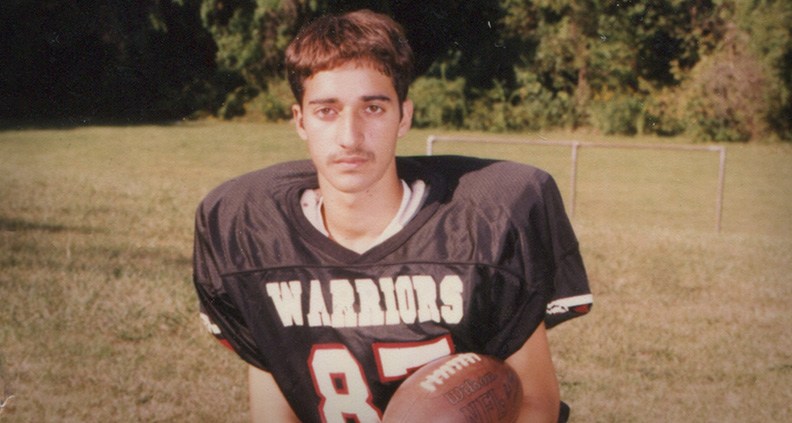

Some docs focus on crimes happening in the past, like Abducted in Plain Sight—which covers events occurring some 40 years ago—while others, like Making a Murderer and The Case Against Adnan Syed, delve into ongoing cases with pending litigation. I asked Callif what a filmmaker should consider when producing a documentary about a criminal case that’s still ongoing.

Callif: “It’s a much easier and less risky proposition to present a case that’s settled. You have access to more information (court transcripts, books, news stories, etc.) An ongoing case is trickier as you don’t have a determination and you also—typically—have less available information. You need to be careful in your storytelling to either A) tell a balanced story of both sides, or B) make it clear that what you are depicting is one side of the story. With Making a Murderer, the filmmakers received a lot of backlash after Season One premiered for not presenting the whole story, and for the series being biased. The truth was that no one on the State [of Wisconsin’s] side would talk to the filmmakers. In Season Two, the filmmakers were very sensitive to this as they wanted to tell an accurate story, and they presented the opposing viewpoint whenever they could.”

THE STORY YOU REALLY WANT TO TELL

Most filmmakers will say that, first and foremost, you must be committed to the story. You are about to invest months—and probably years—of your life to the project. It better be something you’re passionate about. I asked Borgman if there are any red flags that a documentarian should be on the lookout for when doing initial research and in talking to potential subjects whose story would be the focus of a documentary.

Borgman: “I think the red flags that any filmmaker needs to look out for is whether or not someone is asserting a personal agenda, and if [that agenda] lines up with your film. That may not be a bad thing, but if you want to make a different film than they [the potential subjects] do, it can be quite challenging. It’s also always a great idea to get a lawyer onboard early to help assess what legally you can and cannot say. The meetings that I had with the Brobergs [Abducted in Plain Sight’s subjects], both in person and on the phone, were to gauge whether or not they were ready and prepared to tell their story. I tried to fill them in on expectations they may or may not have and—from a creative aspect—if they were compelling and interesting characters that could drive the film.”

A FACT-FINDING MISSION

Compelling storytelling demands rising action. Whether that’s depicted through internal or external conflict may be a mater or choice or circumstance for a true crime documentarian, but facts are definitely something you do not want your film coming into conflict with. When asking Callif what steps a filmmaker needs to take in order to protect themselves—and their project—from legal action, she gave this advice.

Callif: “The ultimate product needs to be thoroughly fact-checked to avoid any potential defamation claims. We require our filmmakers to provide annotated transcripts with reliable source material—preferably two sources—for each factual allegation made in the project. Making a true crime show is not an easy task and the filmmakers need to be prepared to do research, be able to support the assertions made in the film with reliable sources and be prepared to receive pushback. If the people on the team are good journalists, they’ll be fine. But don’t approach this thinking it’s easy.”

MEMORY VS THE TRUTH

Everybody has his or her own point of view. But the truth is the truth and facts are facts—right? I asked Borgman how, with decades of experience, she goes about getting subjects to tell the truth—especially around a sensitive subject like criminal violence.

Borgman: “A lot of times people have their way of telling their story, because they have told it that way for a long time. It’s always good if you can break that rhythm by digging a little deeper into details of the story that they may not have ever been asked about before. The story of Abducted in Plain Sight was 40 years old, so memory played a critical role. There were certainly some memories that were clouded, and stories remembered a dozen different ways, but we were lucky—we had court transcripts to check to see what lined up.”

TREAD LIGHTLY, BUT DIG DEEP

One final sage piece of advice, from Borgman:

Borgman: “True crime docs take on many different shapes. But when there is a crime involved, there are usually huge emotions attached. Showing sensitivity to those emotions while still digging deep and exposing the truth… figuring a way to do both respectfully is very important.”

To watch Callif and Borgman further discuss topics pertaining to documentary film and legal protection, check out the full-length panel Documentary: Safety, Security and Sanity panel from the 2019 Film Independent Forum.