Hacking Film: Super VHS and How Consumer Gear Built A Generation of Filmmakers

In 1977, the phone rang in our kitchen. My mom answered then handed it over to me. There was a woman on the other end, She told me I’d won a prize at our local Safeway raffle. I lost my mind, certain that I’d just won a gas-powered go-cart “Shaggin’ Wagon” custom model that looked like a mini-Mystery Machine from Scooby-Doo.

Nope.

She told me I won second prize: a Polaroid SX70 Land camera and five packs of film. I was confused. I was five and had no idea what that was. But I used it to take pictures of everything… and I haven’t stopped.

I’m not alone. The consumer photo gear of the 1980s and ‘90s was the gateway drug that hooked countless kids on filmmaking. For this month’s Hacking Film, I reached out to a few different filmmakers to learn what gear got them started and combined that info with a brief history of how consumer camera gear evolved to the point that the distinction between amateur and professional equipment is no longer relevant. So—how’d it all happen?

DISPOSABLE FILM

Disposable 35mm cameras, the ones that cost as much as a roll of film, opened the door for many filmmakers. Suddenly, you didn’t have to own a camera to be able to take pictures.

For cinematographer James Laxton (the Film Independent Spirit Award-winning DP of Moonlight) the disposable camera was how he took his first picture:

- “My dad always loved the cheap disposable automatic still cameras that one buys from drug stores. I think he’s probably the only person keeping that business afloat. When I was about 10-years-old, my family was spending time in Los Angeles and my dad asked me to take a picture of him and mom against the sunset. When we got the photo we all loved the way it came out. My parents looked so happy against the sunset and it felt so good seeing them represented with such beauty. Looking back it was the first moment I remember being impacted so heavily by the power of photography.”

And for Andrew Ahn (winner of this year’s John Cassavetes Spirit Award for Spa Night):

- “The first camera I used was a disposable camera, the kind that you use once, develop and then throw away. I was really into them throughout middle school.”

VHS DECKS SET THE STAGE

For 50 years, the TV image was a fixed size: 640 x 480 pixels, every 30th of a second or 300K dots worth of glowing phosphor. So 9.2 million glowing dots of information every second, beamed to your retinas. That was the resolution on your biggest projection screen TV at Shakey’s Pizza, or your smallest Sony Watchman portable CRT.

Contrast that with what you got in the theater for a first-run, 35mm feature film, shot anamorphic, with the image filling your entire field-of-view. Rich, deep color and catastrophic sound system ringing in your ears.

Video was nightly news, TV sitcoms and Saturday morning cartoons, punctuated with endless commercials. What was on the screen depended on the time of day, like a kind of entertainment clock in our living room.

Movies were events viewed in special places, with a ritual and a reverence. Movies were cinema, TV wasn’t. Each knew their place and we were at the mercy of studio release schedules and ever-changing broadcast lineups. Then consumer videotape happened and screwed the whole operation up.

Thank God.

The very first consumer video cassette decks, the Betamaxes and VHS machines, could record as easily as they played and included built-in TV tuners. From day one, they were designed to capture and record content right out of the air.

The studios lawyered up and sued Sony for building copyright infringement machines. Mr. Rogers (yep, the one from PBS) argued on behalf of the machine-makers and the Justices agreed. It was okay to record TV with your VCR. The studios quickly switched gears and sold tape copies at extraordinarily high prices to special video stores that rented them. I worked in one in the ‘80s. A lot of aspiring filmmakers worked in video stores in the 80’s.

TV tech hadn’t changed. It was still a duller, low-bandwidth version of cinema. Access to films outside the theater was changed forever. Small towns could have libraries with thousands of titles from art house to Wrestlemania. We accepted the dim image of VHS as cinema. Videotape changed how we watched movies and soon, how movies were made.

THE CAMCORDER

Just as a VHS consumer deck played home movies and studio releases alike, filmmakers began making movies with vacation camcorders. Some of these filmmakers were literally children using their parent’s home units, like the Duplass Brothers.

- “Our first camera was a family VHS 2-piece system camera connected by cable to the VTR in the early ‘80s. It was a beast. Our company logo is essentially Mark and I using that thing.” -Jay Duplass

For many of us growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, consumer-grade video gear was the first “movie camera” we ever touched. 8mm and 16mm film formats were hard to come by, expensive to process and required at least some training in photography.

Video cameras, on the other hand, were immediate and largely automated. All we had to do was turn on the camera, point it at something and hit the red button. Very few of us thought about exposure or frame rate. We just pushed buttons and twisted focus rings until it looked right in the eyepiece. It was interactive image making.

Around the same time, grown-up indies were also beginning to experiment with using video gear rather than celluloid. Rob Nilsson used professional TV production gear (Beta SP) for his film Heat and Sunlight, which won the Sundance Grand Jury Prize in 1988.

PROSUMER

The Super Video formats of the early ‘90s, SHVS and Hi8, were supposed to crush high-end professional video production by offering a much-improved image and far less-expensive gear to videomakers.

They did not.

TV production companies didn’t suddenly dump Beta SP gear in favor of Hi8 camcorders for the same reasons they didn’t dump them for VHS or 8mm video. While the image was better than VHS, it was still kind of terrible. At least there was now professional-quality editing equipment available for a fraction of the cost of broadcast gear. While high-end video production wasn’t “disrupted” an entirely new class of media makers and organizations, newly empowered by these tools, was created. But professionals knew their days were numbered.

In 1991, I was 19 and a student at UC Berkeley. I got into a yearlong “filmmaking” apprenticeship at a grassroots video organization off-campus. Everything I learned about filmmaking that year I learned with a Panasonic AG450, a Super VHS “prosumer” model.

I made my first short, a documentary about student organizing at Berkeley. It was framed as a faux “dis-orientation” video intercut with riot footage set to Disposable Heroes’ “California Über Alles.” I screened it for a few hundred fellow students at an event on campus and was so nervous I couldn’t stay in the auditorium. They laughed and cheered in all the right spots. There was no turning back after that.

Mini DV

Then, a whole bunch of new digital video formats just kind of jumped on the scene all at once. In 1995, Sony introduced a remarkable camera, the “VX1000” (followed by the VX2000 and VX2100).

The camera was an expensive handycam-style camcorder, but not anymore expensive than the upper range of consumer gear at the time. The features it shipped with were unheard of. The VX1000 had three image sensors, so it was a “3-chip camera”, which put it into the broadcast realm and it used a brand new consumer format: “miniDV”.

MiniDV was the first consumer digital video format and it changed the quality of low-budget video production overnight. No more image degradation or “generational loss.” Says Silas Howard (By Hook or by Crook, Transparent):

- “I made my first feature (which was my very first film) in 1999 on a Sony vx2000. We were inspired by Dogme 95 (Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration and Harmony Korine’s Julian Donkey Boy) but it was so video! We had to use much After Effects grain and flicker to make it work.” -Silas Howard

The VX series also had a brand-new kind of plug called “Firewire”. We did very little with this new port for the first few years because we had no place to plug the cable into. Then, the iMac SE was released by Apple. I could connect the VX1000 to my cheap iMac with a $12 cable. Suddenly your dorm room all-in-one computer was a post-house.

There was an explosion of miniDV cameras after that. They showed up everywhere. Making a film on video meant “DV”—even if you eventually transferred it to 35mm for festivals:

- “The first film we got into Sundance with (This is John, 2003) was shot on a 1-chip Canon from the late ‘90s with a broken pixel. We up-ressed to film and it looked like hell, but we played Sundance nonetheless and got an agent and a lawyer out of it.” -Jay Duplass

- “My first camera was a Panasonic AG-DVX100E. I still immediately remember all those numbers and letters because it was a really big deal for me to buy that camera! We bought it to make a short film on, and then used it to make my first feature, A Plus D. I still have it to use as a tape deck to play all those old Mini DV tapes that otherwise would never be able to be played. Not that I actually play them, but I like knowing I have the option when I’m an old lady.” -Amber Sealey (No Light and No Land Anywhere, How to Cheat)

CHEAP DIGITAL STILL CAMERAS

Just as digital still cameras replaced film, by the early 2000s videotape and film’s days were numbered. The change came from the bottom. By 2002, most consumer-grade digital still cameras had some version of a “movie mode”—usually some noisy, low-quality image recorded at 640×480, similar to VHS. Just good enough for kids messing around.

“The first camera that I owned that I could create moving images with was a Nikon Coolpix 4500. It’s an ancient digital camera from the early 2000s that had a video setting. I created film parodies with my friends in high school. Then in college, I got my hands on a Bolex and I was hooked.” -Andrew Ahn

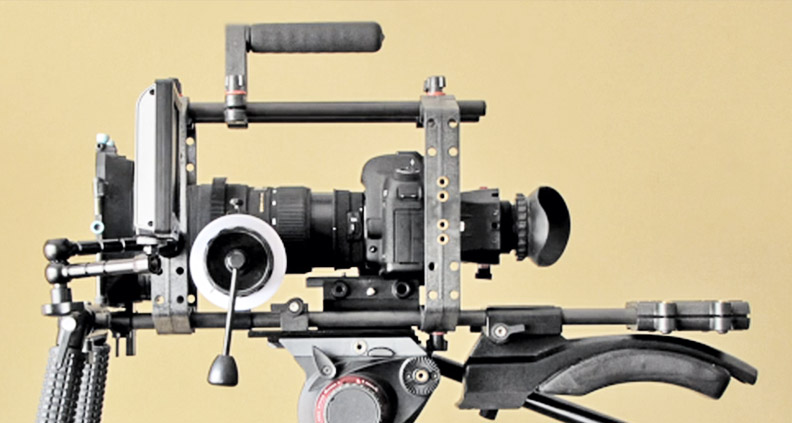

THE CANON 5D MARK II

In 2008, Canon killed video camcorders and 16mm film. I don’t think they meant to. They added a video recording feature to one of their high-end DSLR still cameras, the Canon 5D Mark II (5DM2). A Video option on lower-end digital cameras was common, but on “professional”, cameras they were not. This was added to the 5DM2 for journalists that needed to shoot a little video to go along with the mountain of stills they shot.

Then filmmakers got a hold of the 5DM2. Now there was a camera that shot 1080P HD video with a full-frame sensor. That meant the controlled, shallow focus of film could be replicated on a video camera. Until this moment, video cameras had tiny sensors rendering everything in focus all the time, while a 35mm film plane allowed for greater control. The last ingredient for the “film look”, a large imaging plane, could be had for 2500 bucks. Also, here was a video camera with a ridiculous amount of interchangeable lenses. Within 18 months of the 5DM2’s release, Canon added a 24P frame rate option. Film students rejoiced and piles of 16mm film gear got dumped on Craigslist.

- “My first short film was shot on 16mm on an Arri in film school. Whereas my first feature film, Mosquita y Mari, was shot on the Canon 1D which belonged to my cinematographer Magela Crosignani.” – Aurora Guerrero

The popularity of video-capable DSLR’s spread from no-budget indies to professional TV and filmmaking. Within a few years of the 5DM2’s release, entire seasons of television were being shot on it.

It took nearly three decades, but it happened: video replaced film on nearly every single link of the filmmaking production chain. And it wasn’t a shift that was driven by the camera companies. They were the followers. No, it was the filmmakers—the countless number of people who used the “wrong” kind of gear to make images.

Learn more about the evolution of filmmaking tech, including where we might be headed next, by checking out more of Eric Escobar’s Hacking Film series.

To learn more about Film Independent, subscribe to our YouTube channel. And be our friend on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. To learn how to become a Member of Film Independent just click here.